To the layman’s eye, the recent results of Tunisia’s legislative elections read like the triumph of progressive secularism over backward Islamism. Champions of modernization and secularization theory, in Arab and Western media alike, have hailed the victory of Nidaa Tounes (the Call of Tunisia), a conservative patchwork movement composed of ancien régime figures, technocrats, and leftists, united under the vague banners of Bourguibism and anti-Islamism. The Islamist movement of Ennahda, the incumbent, had been in power since October 2011. I argue that teleological understandings of history and triumphalist narratives of secularism’s victory over Islamism obscure the real dynamics at play in the Tunisian socio-political scene. They also obstruct a more constructive understanding of the lessons the bon élève of the “Arab Spring” has to offer.

Tunisian Debates, French Anxieties

Paris, Tuesday 28 October: At Radio France Internationale (RFI), much of the news report deals with the surprising defeat of Ennahda in the Tunisian elections. The journalist calls the radio’s reporter live from Tunis, immediately echoing the question most of his colleagues have been constantly repeating since the beginning of this week: “(…) On a conclu que le parti gagnant, Nidaa Tounes, était laïque, c’est si simple que ça?”

“Is the winner, Nidaa Tounes, a laïque party?” What an odd question. Laïcité is a historically rooted and exclusively French concept that emerged as an analytical category in opposition to the Catholic clergy. Though scholars differ on the specifics of the concept’s genealogy, they all take the French Revolution as its foundational moment. For political scientist Ahmet Kuru, a scholar of comparative secularism, laïcité emerged as a revolutionary reaction to the Catholic clergy’s support of the crumbling monarchy.[1] Kuru argues that it is this alliance between the religious establishment and the counter-revolution that is at the inception of laïcité. French sociologist and historian of laïcité Jean Baubérot locates its origins in the subsequent “guerre des deux Frances”—a long-standing struggle between a monarchist, catholic, and conservative vision of France and a republican, secular, and left-leaning one.[2] For Baubérot, the second vision won the struggle following the two waves of secularization, respectively of education with the Jules Ferry laws of 1881-1882 and of state-church relations with the law of 1905. However diverse theories tracing the emergence and genealogy of laïcité as a concept may be, there is little doubt that it is a singularly French idea. Perhaps the most obvious proof of its singularity is the extraordinary difficulty anyone who attempts to translate it is faced with. Some in political science have equated it to some sort of “active” or “aggressive” secularism in English. Tunisians have simply arabized the word into la’ikiya, carefully steering away from culturally conflating it with any local concept.

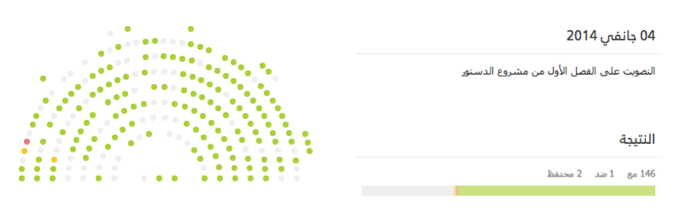

In reality, since independence in 1956, if the relationship between Islam and the state has been a central question for intellectuals and government officials, laïcité has hardly played any role in Tunisian politics. When the National Constituent Assembly voted on Article 1 of the Tunisian constitution, which enshrined Islam as the established state religion, nearly all of the 217 MPs were in favor of it.

[Results of the vote on Art.1 of the constitution. All green seats are votes in favor of it. (Credits: Marsad.tn)]

Habib Bourguiba himself, in a famous interview with a French journalist—already obsessed with laïcité at the time—explained that the Tunisian state could not be described as laïque: “It is a state that is at once Muslim and progressive, this is what constitutes its originality.” Why then would Nidaa Tounes, the self-proclaimed heir to Bourguibian political thought, differ from its spiritual leader on a matter so sensitive as relations between religion and the state? But more importantly, why is French media so eager to impose its own analytical category on the Tunisian case? The polemic seems much more telling of French anxieties than of Tunisian ones.

It is no secret that the model of laïcité, a once nearly sacred concept and cornerstone of French republicanism, is today undergoing a deep crisis—one that is most visible in recent debates on Islam in France. An increasing number of voices within local intellectual circles have started to question the relevance and efficacy of laïcité as a system, or rather as a set of drifting values. It is the name of this set of values, for instance, that the state has the right and, indeed, the obligation to forbid veiled mothers to take their children on school trips. Some have warned against the rise of a discourse of Islamophobia disguised as republicanism and hidden behind the pretext of laïcité. Recently, yet another scandal involving Islam erupted when performers of Verdi’s La Traviata at the Opéra de Paris threatened the organizers to stop singing if a tourist from the Gulf who was wearing the niqab did not leave the performance. The woman was escorted out along with her husband, in an exercise of French finesse.

Back to Tunisia and to RFI’s interview of its reporter in Tunis. After a few minutes of discussion, it became clear that the correspondent was reluctant to call Nidaa Tounes, laïque: “Tunisians think it is a loaded term that is equated with Islamophobia and the ban on veiling in public schools, they are eager to avoid it.” “That is not very helpful,” the journalist replies, “we must find a word!” What is perhaps most striking about this discussion is not that the journalist feels compelled to situate Nidaa Tounes in a category positioned on the scale ranging from Islamism to laïcité. Rather, that he feels entitled to do so himself, completely disregarding the party’s claims to its own identity. We must find a word! Though the debate revolves around Tunisian elections, it mostly reflects French anxieties.

The French, however, are not the only ones to be anxious. At a time of political uncertainty (speculations on the upcoming presidential elections and the nature of the next government’s coalition abound), Tunisians are particularly vigilant against any foreign meddling in domestic affairs. Especially coming from France. From the outset of the Tunisian uprisings, a series of consecutive ill-inspired diplomatic decisions—ranging from material support to Ben Ali’s police repression in the early days of the revolution to the nomination of Boris Boillon, an impulsive diplomat, to the Tunis embassy—have damaged the image of France in the country. On Friday 31 October, this was confirmed by the hostile reaction triggered by Bernard Henry-Levy’s (BHL) visit to Tunisia. The French intellectual, known both for his unconditional support of Israel and behind-the-scene involvement in the ongoing Libyan crisis, was met at the Tunis airport with a crowd of demonstrators urging him to “go back to France” and “leave Tunisians alone.” Regardless of the real reason behind BHL’s visit, the wave of conspiracy theories that have flooded local media and social networks reveals that Tunisians still have a tense relationship with anything French. One can say with certainty that French media’s relentless focus on the constructed question of laïcité in Tunisia does nothing to help.

Drawing the Right Lessons from the Tunisian Case

Imposing definitive categories on Nidaa Tounes is problematic precisely because, as the RFI example illustrates, it overlooks the party’s own voice and provides ready-made answers to questions about its own identity that it either does not see the need to address (laïcité) or has yet to resolve (secularism). Responding to a BBC journalist’s question regarding whether or not his party was secular, a senior member of Nidaa’s leadership replied: “We are secular which means that we are all Muslims and all equal before the law. We do not mix religion and politics.” The response is ambiguous, and particularly illustrative of the party’s own confusion regarding its stance on Islam and the state. Following its electoral success last weekend, and given the media’s anxious urge to corner it into one of these predefined categories, it is likely that Nidaa will have to make itself clearer on this point in the near future and clarify its position beyond merely “non-Islamism.”

However, this overplayed issue of secularism versus Islamism is not the key stake at play in the Tunisian elections. Though Ennahda, which explicitly emphasizes its religious identity, has kept and perhaps consolidated its loyal and consistent electorate (around thirty percent), it has lost many of its 2011 voters to Nidaa following a tumultuous two years in power. This shows that there is a significant “swing vote” between Islamists and non-Islamists, just as it is the case between Democrats and Republicans in the United States, or between the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) and the Socialist Party (PS) in France. Far from illustrating the inevitable secular teleology of modernization, Nidaa’s electoral success, which largely results from a “sanction vote” against Ennahda, simply reveals that the ideological gap between the two parties’ electoral bases is anything but insurmountable. Hence, the majority could very well fall back into the hands of the Islamist party in the next elections.

The existence of a significant group of “swing voters” is one of the healthiest components of the democratic game. It allows for the accountability of those in power and contributes to the edification of a political meritocracy: parties that run successful campaigns are rewarded in the elections while voters neglect those who fail to impress public opinion. Instead of understanding the results of the elections as secularism’s victory over Islamism, then, it seems both more accurate and more useful to see it as the manifestation of the quintessential expression of democratic exercise: alternation in power. In a symbolic gesture, after the first polls confirmed the election’s results, the head of Ennahda, Sheikh Rashid al-Ghannoushi, called Nidaa’s leader Beji Caid-Essebsi in order to recognize his party’s defeat and congratulate his opponent on his victory.

This gesture is even more symbolic than that of the vote casted in the ballot box. It crystallizes most evidently the true achievement of Tunisia’s democratic transition. In 1991, Algerians voted freely to elect a parliament. After the Islamists of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) won the first round, the military stepped in and took over power following a coup d’état. A decade of civil war ensued. Some twenty years later, the Egyptian military ousted the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood from power, jailing President Morsi and systematically repressing supporters of the Islamist group, forcing it back into illegal underground activity.

In the three cases of Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt, all three have organized free and fair elections that allowed citizens to choose their representatives within a multi-party framework. What distinguishes the Tunisian case is thus not the holding of elections per se. Rather, it is the universal acceptance of electoral results as well as the mutual recognition of the Other as a political adversary as supposed to an ontological enemy. This is why the phone call between the two party leaders is so symbolic.

Looking at the Tunisian elections through the lens of secularism’s inevitable triumph over political Islam thus creates the false impression that the political sphere is structured around the rigid opposition and hermetic separation between the two ideologies. As I have argued, this approach obscures Tunisia’s genuine accomplishments: political accountability and peaceful power alternation. But it can also constitute a danger for the long-term evolution of the country’s transition. After many proclaimed “seculars” or “laïques” the winners of this election, fundamentalist Islamist leaders abroad have reacted by publicly criticizing Ennahda for “letting democracy triumph over Islam” and “accepting unbelievers to be in government.” This rhetoric could very well seduce the most radical among Ennahda’s supporters and weaken the position of those within the Islamist movement who have been committed to the democratic transition from the outset. As a result, constructing an ontological divide between Islamists and non-Islamists by inaccurately celebrating Nidaa as the carrier of Western liberal secularism only contributes to Ennahda’s isolation. Thus quite ironically, it is precisely when Western media think they are celebrating the accomplishments of Tunisia’s democratic transition that they are, in fact, inadvertently working to undermine it.

[1] Ahmet Kuru, Secularism and State Policy Towards Religion, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[2] Jean Baubérot, La Laïcité quel héritage? De 1789 à nos jours, Labor et Fidès, 1990.